You'll compute the day of the week for any date specified. For example, if the user specifies February 9, 2026, your program should report that that is a Monday. You'll have to use selection (if statements) to do some error checking and to translate a number into the name of the day. Don't use lists, loops, try-except, or other constructs we haven't covered yet!

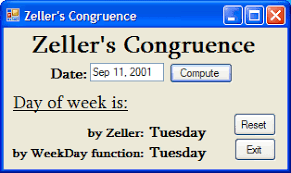

Zeller's Congruence is shown below.

h = ( d + (13 * (m + 1))//5 + K + K//4 + J//4 + 5*J ) % 7

We're computing the day of the week, h, encoded as follows: 0 stands for Saturday, 1 for Sunday, 2 for Monday, 3 for Tuesday, 4 for Wednesday, 5 for Thursday, and 6 for Friday. The other variables used are:

Note: when we say "century" we just mean the first two digits; 2026 is in the 21st century, but we don't mean that.

You will accept the year, month, and day of the month from the user via input statements; don't forget to convert the input string values to ints. You can assume that the values entered are integers.

After you accept each, you'll check (with an if statement) to make sure that it's in the right range; if not, print an error message and exit. This is illustrated below. Note that the year must be greater than 1752; the month must be in the range [1..12]; and the day must be in the range [1..31]. This would allow some illegal dates (e.g., February 31), but don't worry about that. You can assume that the date entered is legal, if it meets these constraints; if it's not a legal date, your program will compute a value that's not right, but that's not your problem. At this point we're not trying to make the program completely robust, just to get some experience using if statements.

To be able to exit your program on an error, you must put your code into a main() function as illustrated in Slideset 1: 34. If you do that you can "exit" by doing a return statement. A return causes you to leave the current function; for the top level function that means leaving the program. The overall structure is illustrated below including accepting and checking the year.

def main():

# Describe what this function does here.

# Accept the year from the user and convert it to an int.

Y = int( input("\nEnter year (e.g., 2008): "))

# If the year is not greater than 1752, print an error

# message and exit the program.

if (Y < 1753):

print("Year must be > 1752. Illegal year entered:", Y, "\n")

return

# handle the month similarly

...

# handle the day of the month similarly

...

# Compute the other variables, including h

...

# Compute the name of the day from h

...

# print the day of week message

...

# You'll need this to run your main program.

main()

Be sure to check the year before accepting the month, and the month

before accepting the day.BTW: I found an almost complete solution to this problem on Course Hero and elsewhere on line. If you find one, don't use it! If it's determined that you copied anyone else's code, you will receive an F in the class and be reported to the Dean of Students. Do your own work. Ask for help from the TAs or instructor if you get stuck.

By the way: I sometimes add comments to these sample outputs to explain something. An example is the comment "Taylor Swift's birthday" shown below. I add those after the fact by editing the output. It's not something that your program has to do.

> python Zeller.py Enter year (e.g., 2008): 1000 Year must be > 1752. Illegal year entered: 1000 > python Zeller.py Enter year (e.g., 2008): 2023 Enter month (1-12): -2 Month must be in [1..12]. Illegal month entered: -2 > python Zeller.py Enter year (e.g., 2008): 2023 Enter month (1-12): 1 Enter day of the month (1-31): 36 Day must be in [1..31]. Illegal day entered: 36 > python Zeller.py Enter year (e.g., 2008): 2023 Enter month (1-12): 2 Enter day of the month (1-31): 6 Day of the week is Monday > python Zeller.py Enter year (e.g., 2008): 1989 Enter month (1-12): 12 Enter day of the month (1-31): 13 Day of the week is Wednesday # Taylor Swift's birthday > python Zeller.py Enter year (e.g., 2008): 1999 Enter month (1-12): 12 Enter day of the month (1-31): 31 Day of the week is Friday > python Zeller.py Enter year (e.g., 2008): 2000 Enter month (1-12): 1 Enter day of the month (1-31): 1 Day of the week is Saturday >

Be sure to test your program before submission. It must also contain a header with the following format:

# Assignment: HW4 # File: Zeller.py # Student: # UT EID: # Course Name: CS303E # # Date: # Description of Program:

If you submit multiple times to Canvas, it will rename your file name

to something like Filename-1.py, Filename-2.py, etc.

Don't worry about that; we'll grade the latest version.

x

if month == 1, 2:

...

That doesn't work. It's interpreted by Python as:

if month == (1, 2):

...

which is comparing the month to a tuple of values, which is almost

certainly False. Similarly,

if month == 1 or 2:won't work. This is interpreted by Python as:

if (month == 1) or 2:Any non-zero integer is treated as True in a Boolean context. So that test is always True, which is not what you wanted. What you probably meant was:

if month == 1 or month == 2:

...

(Think about what happens if this used and rather

than or.)

You can assume. When an assignment says that "you can assume" something about the input, that just means that you don't have to check it. If the user enters an input that doesn't meet that assumption, the program can crash or behave badly. That's not your problem.

For many of the assignments this semester, we'll say that you can assume certain things about the inputs, often because you don't yet have the skills necessary to check for certain errors. But if you get a programming job, you should always validate the inputs as much as possible. In general, it's bad programming practice to allow bad inputs to crash your program; it means that your program is not robust. Later we'll insist that you "validate" some inputs, meaning to assure that they do meet specifications. For example, you could ensure that the value entered for month (remember it's a string) is a legal value by:

# Check whether the value entered is a string representing one of

# the numbers from 1 through 12.

if monthEntered != '1' and monthEntered != '2' and ... monthEntered != '12:

< handle the error here >

else:

# Input is legal, so turn it into an integer.

month = int( monthEntered )

But if we say that you can assume that it's an integer, then the test

becomes much easier (once you apply int()):

if (m < 1 or m > 12):

< handle error here>

else:

...

BTW: if you just did the above, your program still might crash if the input

were spurious, like "abc".

month = int( input( "Prompt: " ) )

It wouldn't crash here if "-192" were entered. But it would probably

fail later on or give unexpected results.

There are more compact and more robust ways to do this, but this would work. Note that we're not checking for all possible errors: spurious input like "abc", dates like February 30, etc. Production code should really never crash due to erroneous user input, but we're not to the point of writing production code yet.

> cal

January 2023

Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

8 9 10 11 12 13 14

15 16 17 18 19 20 21

22 23 24 25 26 27 28

29 30 31

> cal 2 2023

February 2023

Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa

1 2 3 4

5 6 7 8 9 10 11

12 13 14 15 16 17 18

19 20 21 22 23 24 25

26 27 28

It's pretty smart; here's the entry for September, 1752, the month the

Julian calendar was replaced by the Gregorian calendar in Britain and

its colonies (including the U.S.). Eleven days were dropped to make an

adjustment. This is just for your amusement and maybe a way to win bar

bets or amuse your friends.

> cal 9 1752

September 1752

Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa

1 2 14 15 16

17 18 19 20 21 22 23

24 25 26 27 28 29 30

BTW: this is why we're only making your code work for years after

1752.